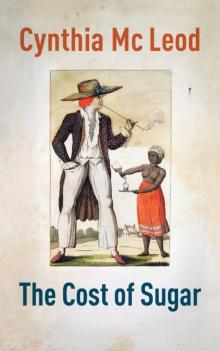

- Home

- Cynthia McLeod

The Cost of Sugar Page 2

The Cost of Sugar Read online

Page 2

Father Levi smiled at Rebecca as she took her place at the table. “Ready for the trip?” he asked, exaggerating the movement of his lips.

Rebecca shook her head. “I’m not going.”

“Oh come, why not?” asked Pa Levi.

Something like “Don’t want to” sounded as Rebecca shook her head again. Elza looked at Rebecca. She could well understand that Rebecca didn’t feel like going. Why would a deaf person want to go to a party that comprised mainly chatting, gossiping and playing music? She would be able to follow nothing and would just end up feeling lonely. She often felt sorry for Rebecca; what could her future be? Even now, at twenty-one, she was an old spinster, and was destined to remain so for ever, for who would marry a deaf woman? Above all, she hardly ever encountered a young man.

Now from the rear veranda came Aunt Rachel’s voice asking Maisa and Kwasiba if they had looked after everything for the misses. Entering the dining room, Rachel asked immediately, “Where’s Sarith?”

“Oh, she’ll be here,” answered Elza. Whatever Sarith might do, Rachel never got angry with her, for she was her mother’s darling. Elza had often thought that this was due to Aunt Rachel’s surprise at having borne such a beautiful daughter. And now Sarith came dashing down the stairs. She had some rouge on her cheeks and looked really lovely in her light-yellow dress. The naturally black curls danced around her ears, but with an angry look she said to her mother, “That stupid Mini-mini: I told her to wash my pink gown, but she hasn’t done it and now I can’t wear it.”

“You have plenty of others,” replied her mother.

“Yes, but I wanted to put that one on.”

And then impatiently to Kwasiba:

“I don’t want that egg; take it away. I want pancakes.”

“Yes misi,” said Kwasiba, and she hurried off to the kitchen to tell Ashana that Misi Sarith wanted pancakes, not an egg. Pa Levi had in the meantime left the table and had gone to the waterside to see whether the boat was ready and the luggage properly loaded.

Elza got up and went to the rear veranda. She wanted to say farewell to Ashana before they departed. Standing on the veranda, she looked towards the outside kitchen at the back of the grounds where the cook was hastily making pancakes for Sarith. She wondered again what it was that was making Sarith so cross and bad-tempered lately. When a little later Kwasiba came towards the house with a plate of pancakes, Ashana emerged from the kitchen.

“Ashana, I wanted to say goodbye,” called Elza. Ashana hurried to the veranda.

“Look after yourself well now, misi, I’ll miss you.”9

“Oh, it’s only a few days, Ashana.”

“Take good care of your father: I hope he won’t quarrel with that old woman.”10

Elza laughed. Just like Ashana, she knew that no-one could prevent grandma using her sharp tongue. But as always, papa would survive.

“I’ll have Koki prepare a tasty banana soup when my misi returns,”11 Ashana continued.

“Very good, Ashana, keep well,” and Elza nodded to Ashana with a smile. At the door Elza turned for a moment and added, “Look after Misi Rebecca, won’t you!”12

“Yes misi,” replied Ashana. She would look after Rebecca; she liked her a lot. It was a very different story with Misi Rachel and Misi Sarith. As far as Ashana was concerned they could stay away for ever.

SARITH

The tent boat glided slowly over the Suriname River, powered by a crew of eight oarsmen. Under the canvas roof sat Uncle Levi, mother Rachel, Elza and Sarith. Behind Rachel, Kwasiba and Mini-mini were sitting, and in front of Elza and Sarith sat Maisa. Sydni, Uncle Levi’s personal slave, sat near the stern of the boat and now and then conversed softly with Kofi, who was seated right at the back, steering the boat.

Sarith sat with her chin in her hands, gazing ahead. In fact, she had said nothing since their departure. Now and then Elza said something to Maisa or her father, and she occasionally cast a sideward glance towards Sarith, but she looked so cross that Elza found it better not to speak to her.

When Elza had called that morning, “Sarith, are you awake?” Sarith had replied, “Let me sleep on a bit more.” She didn’t want to sleep, however – she had long been awake – but she did want to think about what she would do today. She must get to speak to Nathan alone, but that would not be easy, since he would of course be in the constant company of his betrothed Leah, that pale, puny Leah. What was she in comparison with her, Sarith? She was a hundred times more beautiful than Leah. Oh yes, she was quite aware of that: she was beautiful, far more beautiful than all the young girls she knew. Everyone said it, and she knew from the way all the men, young and old, looked at her.

Nathan, the yellow-belly, was engaged to Leah after all. And again Sarith recalled what had happened rather more than a month ago. There had been a huge party at the Eden Plantation, near Paramaribo. That was the plantation belonging to Nathan’s parents. The occasion was the Bar Mitzvah of the youngest son, the thirteen-year-old Joshua, Nathan’s youngest brother. Many guests had lodged there for a week or more: the older couples in the plantation house, the young ladies with their slave-girls in the unoccupied overseer’s lodge, and the young gentlemen in a warehouse that had been refitted especially for the occasion. The nineteen-year-old Nathan, the oldest son, had behaved as a real host and had made no secret of his amorous feelings towards Sarith. He and Sarith had spent several afternoons together in his room while everyone was resting. Many a time they had passionately kissed and hugged, and each time they both looked forward to the next moment they could be together. Nathan adored her. Infatuated, he had told her time upon time how much he loved her and that he wanted no-one else but her. But for the moment they would have to keep their liaison a secret, for it had already been decided by his parents that he should marry Leah Nassy. Sarith would have to grant him some time, and then he would make it clear to his parents that he could not marry Leah because he was in love with Sarith.

And Sarith had indeed given nothing away. With a surreptitious smile she had listened to the chatter of the other girls, especially Leah, and had seen how she blushed every time Nathan’s name was mentioned. Children, they were all just children, and even Elza her stepsister was really just such a child. Now she, Sarith, knew much more about life. Nathan was not the first with whom she had played the game of love. From the age of thirteen she had lived for two years in the town13 with Elza at the house of their sister, Esther. And then she had become friends with Charles van Henegouwen, the brother of one of her classmates at the French School. Many were the afternoons she had spent in the company of Charles. When his parents were out visiting, she and Charles had always managed to arrange to be alone in the house. Until his parents had found out, probably given away by one of the slave-girls. The result was armageddon. Esther was livid and had summoned mama. Sarith and Elza had to return immediately to the plantation and Charles was sent to Holland by his parents. Oh, she understood perfectly well why. She was a Jewess and Charles was not. Many well-to-do Christian plantation owners wanted as little as possible to do with Jews, as if they were an inferior type of person. Ridiculous: they were all whites, after all!

Once back at the plantation, mama had delivered a complete sermon and had tried to find out exactly what had been going on between her and Charles, but Sarith wasn’t stupid enough to tell all. She could hardly admit to her mother that they had slept together on at least six occasions, and so she had said that they had just kissed. Mama had heaved a sigh and had said that a girl could never be too careful, and must absolutely not do anything stupid. Oh yes, that is how it was: men and boys could do anything and everything, but girls could do nothing. They had to take their place in the marriage bed as innocent and naïve angels.

After Charles there had been a young captain, who had been ordered to inspect a military post in the hinterland of Joden-Savanna. He had fallen ill there and had been taken to Joden-Savanna. A whole month he had lain there sick in her grandparents’ house. Durin

g that period she and Elza had by chance lodged at Joden-Savanna for two weeks. At first they had both stayed with Grandma Fernandez, because Sarith’s own grandmother Jezebel would not have two young girls sleeping in her house while the captain was lying there sick. But when the captain was beginning to recover, Sarith had visited him regularly and what in fact had begun as a bit of fun had ended as a full-blown love scene. Just once, for the captain had said afterwards that he regretted what had happened. He was married, had a wife and children, and he asked Sarith to forgive and forget him.

And a little more than a month ago it was Nathan. Nathan, who had told her that he would explain to his parents why he could not marry Leah. Two weeks earlier Uncle Levi had happened to be visiting Paramaribo for a few days and returned from town with the news that Nathan was officially engaged to Leah Nassy. Leah’s parents had given an intimate dinner party for the family and a few friends. Since Uncle Levi was in town, he was also one of the guests, along with Sarith’s sister Esther and brother-in-law Jacob. It would not be a long engagement, for Nathan and Leah would marry within two months. How furious Sarith was upon hearing all this! She had stormed to her room, had wept, smashed things, thrown the bedding on the floor, stamped with rage. In short, she was livid, and Mini-mini was more than once the unfortunate who suffered at first hand. Everything the slave-girl did in those days was wrong, and on several occasions she had suffered a resounding thick ear from her mistress. Amazed, Elza had asked time and again what was the matter, but each time Sarith had sullenly replied, “Nothing,” or, “It’s none of your business.”

Now she would be seeing Nathan in a few hours’ time, and then everything would turn out all right, because she would demand of him that he, there at Joden-Savanna, tell his family and everyone else that he loved her, Sarith. And he would do what she said, because he loved her. He simply had to do it, and that stupid, plain Leah would get a nasty surprise and perhaps burst into tears and faint. A pity that there was no chance in Suriname to elope with someone. In another country, in Europe for instance, you could run off, in a carriage or on a horse, far away to another town and get married there. But here, where could you go? Except for the town and the plantations it was all jungle. Scary jungle with dangerous wild animals and Maroons – escaped slaves who murdered white people.14 But all right, once Nathan saw her he would of course be so in love with her that he would do what she said and everything would turn out as it should. That was the reason she had really wanted to put her pink dress on that morning. Mini-mini must wash that dress as soon as they landed at Joden-Savanna, and then she could wear it tomorrow, on the feast-day itself.

When, some hours later, the boat moored at the jetty at Joden-Savanna and the company was being welcomed by the many guests who were already there, Sarith looked around straightaway to see whether she could see Nathan. But she saw neither him nor Leah. Leah’s parents she did see, and they told her enthusiastically that Leah together with Nathan would arrive only the next day, since they had stopped off at Rama Plantation and would spend the night there.

Rama was scarcely an hour away from Joden-Savanna, and a cousin of Nathan’s was the owner there. Leah and Nathan would be at Joden-Savanna the next day well before the start of the service in the synagogue. Until that time, Sarith would just have to be patient. Now, at any rate that gave her time to think over carefully everything she would say to Nathan.

JODEN-SAVANNA

When the boat bearing Nathan and Leah moored at the jetty at around 9 o’clock the next morning, there turned out to be other guests on it: Nathan’s cousin, who was the owner of the Rama Plantation, and Rutger le Chasseur, a young man who had been in the colony only a few weeks, appointed as assistant-administrator for a well-known Amsterdam bank. Sarith was dressed in her beautiful pink gown, pink slippers of shiny satin on her feet. When a surprised Elza had seen Mini-mini carefully lowering the exquisite gown over Sarith’s head early that morning, she had asked her stepsister whether it would not be better to let the dress hang ready for the ball that evening. But Sarith had retorted with a short, “No,” and then asked, “Are you coming along to the waterfront?” When the boat moored, Sarith was standing there provocatively on the very end of the jetty. Nathan had turned extremely red when he saw her standing there, but Sarith had no chance to talk with him. Leah’s parents herded the complete company along, first to the house where they would be staying and then to the synagogue. In the synagogue there was not the slightest chance for Sarith to exchange a single word with Nathan, for the women and men sat in separate sections to follow the service.

ELZA

Since all the Jews had gone into the synagogue, Elza just wandered around outside. She had just decided to go and sit on the front veranda of her grandmother’s house when suddenly an unfamiliar man stood before her.

“Shouldn’t you be inside, Miss, uh …”

“Fernandez,” said Elza, “I am Elza Fernandez, and no, I don’t belong there, I’m not a Jew, and you are apparently also not Jewish.”

“No, indeed, me neither, but you do have a Jewish name, don’t you?”

“Yes, that’s because my father is Jewish but my mother is not, and as you may know, under Jewish law only children of a Jewish mother are regarded as being Jewish.”

“Well I never,” the young man continued, “I had never expected to find something as enlightened as a mixed marriage in this far-off Suriname.”

“Maybe you’ll come across a lot more enlightenment during your time here, Mister …”

“Le Chasseur, Rutger le Chasseur is my name; please excuse me for not having introduced myself earlier.”

“How long have you been in the colony?” asked Elza.

“Oh, not so long, about three months.”

“And how has it been so far?”

“Hot, very hot,” answered Rutger. Elza laughed,

“Oh yes, these past months are usually the hottest of the year, though at Joden-Savanna it’s usually not too bad. It’s higher than Paramaribo, you see.”

“Oh yes, I have noticed that. And how do I find it for the rest? Beautiful! Paramaribo is such a lovely, bright town, not large, but pretty, fresh and clean. I’m already beginning to feel a bit at home. Shall we wander down to the river?”

Together they walked and he told Elza how he had come to Suriname as assistant-administrator. His great-uncle, who was the owner of a bank in Amsterdam and also of several plantations in Suriname and Berbice15, had decreed that he, Rutger, should learn the trade of administrator. When Elza remarked that that uncle must be extremely wealthy, Rutger had laughed and confirmed that his great-uncle was indeed very rich. He, Rutger, belonged to the poor branch of the family and was also no heir, since great-uncle had four daughters. His grandmother, who was a sister of his great-uncle, had been married to an exiled Huguenot, which explained his French surname.

Elza in turn recounted how she lived on the Hébron Plantation together with her father, stepmother Rachel and stepsisters Rebecca and Sarith. Her own brother David was already married and had a plantation on the Para River.

“Was that pretty girl who stood next to you on the jetty one of the stepsisters?”

“Yes, that was Sarith,” said Elza.

“What a pretty girl that was,” remarked Rutger. Elza nodded. Yes, Sarith was certainly pretty. Everyone was always saying that. Everywhere they went it was Sarith who was noticed first, and time and time again it was remarked how attractive she was. Yesterday, when they had arrived, everyone had yet again admired her beauty. Aunt Jezebel, Sarith’s grandmother, had said this on many occasions to grandma; Aunt Sarah, Aunt Rachel’s sister, had mentioned it, and Aunt Rachel beamed with pride every time she heard how beautiful everyone found her youngest daughter. The eyes of all the men beheld Sarith with wonder, and one of the older ladies had remarked that Sarith was already fully a young lady, while Elza, of the same age, was still only a girl.

“Do you come to Joden-Savanna very often?” Rutger was asking.

>

“Oh, at least once a year. It’s my grandmother’s birthday today, and it’s important to her that everyone knows that she and the synagogue share the same birthday, and very often this coincides with the Feast of Tabernacles, you see. And so it goes.”

“And do you always have to wait outside when there’s a service in the synagogue?” Rutger repeated.

“Yes, always, but it really doesn’t matter,” answered Elza. “We ourselves have been baptized as Lutherans, because my mother was Lutheran, and as children Pa always dropped us off in the town at Christmas, to stay with our grandfather, our mother’s father. But Grandfather died five years ago, and since then we’ve never been in the church in Paramaribo at Christmas.”

The Cost of Sugar

The Cost of Sugar