- Home

- Cynthia McLeod

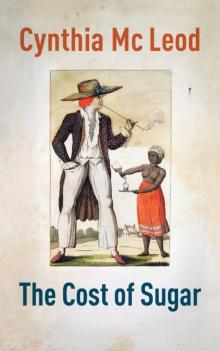

The Cost of Sugar

The Cost of Sugar Read online

PRAISE

‘An invaluable story’ De Telegraaf

Cynthia McLeod

THE COST OF SUGAR

The Cost of Sugar is dedicated to Helen Gray.

Without her friendship, willingness and patience this book would never have been written.

C. MCLEOD

WASHINGTON D.C., JULY 1985

Contents

PRAISE

Title Page

Dedication

CHAPTER I

CHAPTER II

CHAPTER III

CHAPTER IV

CHAPTER V

CHAPTER VI

CHAPTER VII

CHAPTER VIII

CHAPTER IX

CHAPTER X

CHAPTER XI

CHAPTER XII

CHAPTER XIII

EPILOGUE

Notes to the various Dutch editions

LITERATURE CONSULTED

GLOSSARY

BLURB

About the Author

Copyright

Dear Reader,

The Cost of Sugar was first published on 28 October 1987 and the first day of sale was on 30 October 1987. I still remember that a colleague from the high school where I was teaching said to me a few days before the presentation, “If five hundred copies of a book are sold in Suriname, it’s a bestseller.” When I asked her over what period of time, she answered, “Oh, that doesn’t matter, just if five hundred copies are sold, because Suriname doesn’t have a reading tradition.”

I felt troubled and sorry for the publisher, who had printed 3000 books. I already envisaged piles of unsold copies of the book in the bookstore. The facts have proven the contrary. Within six weeks the first printing was sold out and the book had to be reprinted. Many reprints followed. Then in October 1994 the book was discovered by Dutch publisher Kees de Bakker from uitgeverij Conserve who published the book in the Netherlands under licence. Immediately after that, a German version followed. And today we present this special edition in English.

Who could have imagined this? Not me! Who could have imagined that this book would remain the best-selling book in Suriname all these years and also the best-sold book of a Surinamer abroad? And who today would dare to say that Suriname doesn’t have a reading tradition?

The Surinamese community has embraced, cuddled and cherished this book, and this in particular proves that a book, a work, can have a certain value for a community that extends far beyond a literary and/or commercial value. And especially for this I wish to thank all readers in and outside Suriname. The expressions of appreciation that I have received in abundance over these many years have always been heart-warming and an incentive to continue writing.

To my surprise I was honoured by all the bookshops of Paramaribo, which – led by Sylva Koemar – organized a big party in November 2007 to celebrate the 20th anniversary of the publication of my book. It was a delightful evening. I am looking forward to seeing the film being made by director Jean van de Velde and producer Paul Voorthuysen, which is due to come out in December 2012 and will be shown as a four-part series on Dutch television in March–April 2013. In 2013 it will be 150 years since slavery was banned in Surinam.

Thank you for your interest!

Cynthia McLeod, Paramaribo, October 2007/2011

CHAPTER I

THE HÉBRON PLANTATION

Dawn is breaking on the Hébron Plantation, and while the eastern sky is blushing at the caress of the rising sun, the doors of the slave huts begin to open one by one, and small fires can be seen under their lean-to shelters. Faya watra is being made: hot water into which a shoot of molasses is stirred. Here and there an appetizing scent arises from a cooking pot, signalling the presence of an aniseed leaf or some herbs in the water.

Now, outside all the huts, men, women and children are standing, some talking, some just looking around. Eventually they make their way to the southern edge of the plantation, where a canal has been dug at right-angles to the river, serving for both the supply and the drainage of water. Alongside the boathouse, where the river shore slopes gently, they enter the water to bathe: the adults more serious, the children laughing gaily and splashing each other until they’re wet through. With loincloths slung around their wet bodies they return to the huts, mostly in small groups, the children following on, naked. Now it’s time to drink the faya watra. The leftovers from the previous evening’s meal serve as breakfast.

In the hut where the fifteen-year-old Amimba is living with her mother, brothers and sisters, Mama Leida throws a handful of dried herbs into a gourd and pours boiling water over them. This is a drink for Amimba; as happens every month, she is suffering terrible abdominal pains. She has lain on her mat moaning and groaning the whole night through, tossing and turning, now lying, now sitting up. Now she is sleeping a little. Luckily. But Mama Leida herself has hardly caught a wink of sleep the past night.

After the faya watra and breakfast, people begin drifting in the direction of the warehouse, the occasional woman breast-feeding a baby, another with a baby already tied to her back. The warehouse doors are still closed, but it isn’t long before the white overseer, Masra1 Mekers, arrives with the keys. The rations for the evening are now distributed to each family head, and instructions are given for the day’s work.

But first the roll-call. Where’s Kofi? Oh yes, he has a sprained ankle and won’t be going onto the land but will have to work in the carpenter’s shop. Amimba with stomachache? What, again! No messing about! Come here and now, or be fetched with a whip. Why doesn’t Afi have her baby with her? He was sick the whole night long with fever. Afi would prefer to leave him with the nurse today. She’ll give him a herbal bath for the fever. Tenu? Where’s Tenu? Come here! Basya2 – five lashes of the whip for Tenu, thirteen years old, who sees to the chickens. He has stolen eggs. There were six too few yesterday, and the empty shells were still lying next to the chicken-run. Tenu protests vehemently. It’s a lie; he’s stolen no eggs. Didn’t masra know that a huge sapakara3 has been lurking around and has stolen the eggs? If he, Tenu, had indeed stolen eggs, then he wouldn’t have been so stupid as to leave the empty shells lying around near the run, now would he! Even so, five lashes for Tenu! For isn’t it his job to look after the chickens? How had a sapakara managed to steal six eggs if Tenu was there? Of course: because Tenu was not there! Hadn’t he spent half the day yesterday fishing in the creek? Five lashes! And this evening not a single egg missing and Tenu to present the dead sapakara! Five lashes, too, for Kobi, a year older than Tenu and helping Felix look after the horses, mules and cows in the stalls. Kobi cut too little grass for the animals yesterday. And no wonder: he was sitting fishing at the water’s edge along with Tenu! Five lashes, and this evening a double portion of grass to have been cut. That was all.

Once the basya has delivered the lashes the slaves can depart. And after the whip has descended on Tenu and Kobi’s slender, bare backs and the two boys stumble off tearfully to their workplaces, the group, about sixty strong, disperses. The field group, about forty in number, leaves first. This group begins to move off silently, most of the slaves chewing on an alanga tiki4. Two of them are carrying a bunch of bananas on their heads, another a bundle of various root crops for the meal to be cooked in the fields, in two huge iron pots. The basya, with a whip in one hand and a machete in the other, follows at the rear. Another group, comprising six slaves, goes to the sugar mill, a few others to the shed where the sugar is boiled up with water. Yet another group is off to the carpentry shop, two to the boat house, and two of the more elderly to the grounds around the plantation house to ensure, armed with rake, hoe and watering can, that everything there is neat and tidy. Five-or-so women and girls go tow

ards this white house, too, as well as the domestic slaves and the errand boys, and Sydni, the master’s personal slave. The house still presents a rather sleepy prospect, its doors and windows all closed. The overseer, Mekers, goes first to his own house, where his slave-girl has breakfast waiting.

Even before he arrives he is greeted by the mouth-watering odour of fried eggs and freshly made coffee from the laid table. A new day has dawned. For the slaves, a new day of hard labour, a new day in the endless progression of days devoid of the faintest ray of hope.

ELZA

At the front of the splendid Great House, however, not all windows are still closed. An upstairs window is open, and there stands Elza, seventeen years old. She is gazing out over the green lawn that extends from the front of the house right down to the edge of the wide, lazy Suriname River. A lovely morning, the beginning of a good day. Today, 11 October 1765, the family will travel to Joden5-Savanna for grandma’s sixty-fifth birthday. That will be tomorrow, the twelfth of October and at the same time the eightieth anniversary of the synagogue at Joden-Savanna.

Grandma had always been proud that she had been born on 12 October 1700, the day on which the Beracha Ve Shalom (Blessing and Peace) Synagogue in her birthplace in Suriname was fifteen years old. Elza had been looking forward to the coming two weeks. Not so much because of grandma, but for the stay itself and all the parties there would be. Many friends and acquaintances would be there, and many a tent boat had recently sailed by. Sometimes the company had stopped off for a few hours at Hébron Plantation, or had even stayed overnight, since the plantation lay precisely half way between Paramaribo and Joden-Savanna and it was sometimes necessary to wait for high tide. The whole Jewish community in Suriname was in the habit of travelling to Joden-Savanna for a few days around high days and holidays. This year the Feast of Tabernacles fell in the same week as grandma’s birthday. The parties were always enjoyable, even though Elza realized that her situation was rather different, having a Jewish father and a Jewish name, but not herself being Jewish. And there were enough types who were not always that congenial towards her. She often felt a sense of admiration for her father when she considered that he had managed twenty-five years ago to act against his mother’s will. Of course, she wasn’t born then, not by a long chalk, but she had heard the tales often enough, especially from Ashana, her mother’s personal slave.

Levi Fernandez, now forty-five years old, had from the age of twelve, when his father died, been raised single-handedly by his strict mother. She ran the Hébron Plantation on her own, and decided and organized everything. She had everything and everybody beautifully under control: the plantation, the household, the slaves, her son … Or at least that’s what she thought, until he refused to marry Rachel Mozes de Meza, the Jewish girl whom it was assumed, from the very moment of her birth, would be Levi’s wife. The twenty-year-old Levi had confronted his mother like a fiery young stallion. No way was he going to marry Rachel, the daughter of his mother’s bosom friend, who was four years younger than he and whom he had known from childhood. He would not marry her because he was fond of someone else: the seventeen-year-old Elizabeth Smeets, daughter of an army officer, only two years in the colony, without money, without prospects and above all a Christian. That was the first time that Widow Fernandez failed to impose her will on her son. Immediately after Levi had married his Elizabeth, his mother had moved out, returning to Joden-Savanna, her birthplace. She left the Hébron Plantation, to which her son had been legally entitled since his eighteenth year…‘Because it was not her intention to live under the same roof with that Christian person’.

It was nine years before she returned to the plantation, and that was on the occasion of the burial of her daughter-in-law Elizabeth. She had died a few days after the birth of her daughter, who received her name from Elizabeth, and was accordingly called Elza. Had the widow Fernandez perhaps hoped and believed that she might take up the reins of the Hébron Plantation again? Had she perhaps imagined herself holding sway over the slaves, her household, her son, the children, David, then eight, six-year-old Jonathan and baby Elza? That was, however, not to be. Levi treated his mother with politeness and propriety, but the plantation was his and his domineering mother could remain at Joden-Savanna. The children were well cared for by Ashana, Elizabeth’s personal slave, and by Ashana’s daughter, the eighteen-year-old Maisa. When Elizabeth died, Maisa was just starting to breast-feed her second son and so it was no problem to take on the misi’s6 newborn daughter, too. And so it was that the Hébron Plantation remained without a mistress for a good seven years, but with Ashana and Maisa there to look after everything.

Until in 1754 the second son, Jonathan, died at the age of twelve. Such an insignificant mishap, a sharp, pointed stick in his foot. But it turned into something terrible, and Jonathan passed away. And Grandma Fernandez could claim that she had always thought something like that would happen. The children, after all, were being brought up by slaves, were running around the grounds barefooted, playing in the creeks, climbing trees, in short behaving not at all like neat and tidy, white plantation children. But what could you expect if slave women ruled the roost. They had no way of knowing how things should be in a white family. So Jonathan’s death was his father Levi’s fault.

Did Pa Levi give in to all these reproaches? Did he perhaps have real feelings of guilt? Be that as it may, a few months after Jonathan’s death he married Rachel, the woman he should have married fifteen years earlier and who herself was now the widow of A’haron and had three daughters. And so it was that Aunt Rachel moved onto the Hébron Plantation along with daughters Esther, Rebecca and Sarith. Sarith and Elza were about the same age, and it was wonderful for the seven-year-old daughter of the house to enjoy the company of someone of the same age. And now Elza could hardly remember the time before Sarith.

Elza looked out of her window and breathed in the fresh morning air. How beautiful and fresh everything looked from the dew. In a few hours’ time it would be dusty. It was the dry season and there had been no rain for three weeks now. Luckily the lawn was still green, and would remain so, for lo and behold there was the elderly slave Kwasi, already busy watering the lawn with buckets and watering cans. He walked to the jetty, lowering the bucket into the river and filling the watering cans from it. Elza turned round and called softly, “Sarith, Sarith, are you awake?”

“Hmmm, no, yes, oh Elza, let me sleep on a bit more,” came Sarith’s voice from a bed on the other side of the room. Sarith turned her back towards Elza and pulled the sheet over her head.

Soft footsteps in the corridor and a modest knock on the door.

“Yes, come on, Maisa, I’ve been up for ages.”

Maisa entered with a tray with two cups of cocoa in one hand and a bucket of water in the other.

“O Maisa, isn’t it a lovely day today?”

“Yes misi,” answered Maisa with a smile while she placed the tray on the table and filled the water jugs on the two washstands with water. She then went to the cupboard and took out a light-green muslin dress and asked, “Will misi be wearing this?”7

A few moments later Elza had freshened up and was sitting on her bed with Maisa kneeling before her, drawing on her stockings one by one after having put her pantaloons on for her. Thin white cotton down to the ankles, with lace at the bottom by the legs. Thereafter a white cotton batiste blouse and two underskirts. Another discreet knock on the door. Upon hearing a “Yes” from Elza, a beautiful brown girl came in. This was Mini-mini, the fifteen-year-old slave-girl who would have to dress Sarith.

Elza peered at the bed, where there was still no sign of movement, and said, “Sarith, get up now: you know that papa wants us ready in time.”

“Oh, blow – all this moaning and nagging, too.”

Upon which the sheets were pulled aside in one single jerk and landed on the floor, and Sarith strode angrily towards the small room where the chamber pots stood. Elza and Maisa exchanged fleeting but meaningful glances and th

e timid Mini-mini remained standing near the wall while her head dropped and she shuffled submissively over the floor. Elza sighed. Sarith was in a bad mood again, as she had so often been of late. What was up with Sarith? In the past she told her everything, but now no more. But so be it, she wasn’t going to let it worry her. Maisa motioned to Elza to sit down and she lit a candle on the table. Then she held a small curling iron in the flame and began carefully to curl her mistress’ hair.

When Elza went into the dining room downstairs a little later, only her father was sitting at the breakfast table.

“Good morning, papa.”

“Good morning, dear little miss; are you ready? We’ll be leaving the moment the tide is right, and that’s in three-quarters of an hour.”

The elderly slave woman Ashana entered with a plate bearing freshly fried meat, eggs and bread. She set everything down in front of Elza and remarked with an approving nod, “Oh Misi Elza, aren’t you looking pretty!”8

Soft footsteps could be heard, and Rebecca now came in from the rear veranda. Rebecca, twenty-one, was Aunt Rachel’s second daughter. She was deaf. At the age of nine she had contracted typhoid fever. She had survived this, but since then could hardly hear anything. She could still speak, but in a monotone, and she spoke very little. Rebecca lived her own private life, quiet, withdrawn, mostly in her room, where she read, painted, drew and made dolls. Lovely dolls. Everyone who saw them said she could start a business with them. Just now and then Rebecca made a doll to order and accepted some money for it, but she often gave them as presents to people she knew and most of the dolls were simply displayed in her room. People didn’t bother much with Rebecca. She hardly ever saw her mother and she said only what was really necessary to her sister Sarith and her stepsister Elza. The only people she did talk with were her stepfather Levi and her slave-girl Caro. When the widow Rachel A’haron had moved to Hébron Plantation ten years earlier she had brought with her a number of slaves: Kwasiba and her two daughters Caro and Mini-mini, who were at that time eight and five years old, and in addition her own personal slave-girl, Leida. Caro was Rebecca’s slave-girl. She followed her mistress everywhere and helped with washing paintbrushes, mixing paint, sewing dolls’ clothes and so forth. The fifteen-year-old Mini-mini was Kwasiba’s pride and joy. Obviously of mixed blood, Kwasiba had never revealed who Mini-mini’s father was, but people suspected that it must have been Rachel’s late husband Jacob A’haron or his son Ishaak. In any event, Mini-mini had brown skin, slightly curled hair, a slender face and large, dark eyes. Mini-mini was Sarith’s slave-girl, and no-one seeing them together could avoid the impression that there was a striking resemblance in face and figure.

The Cost of Sugar

The Cost of Sugar